- Home

Edition

Africa Australia Brasil Canada Canada (français) España Europe France Global Indonesia New Zealand United Kingdom United States Edition:

Global

Edition:

Global

- Africa

- Australia

- Brasil

- Canada

- Canada (français)

- España

- Europe

- France

- Indonesia

- New Zealand

- United Kingdom

- United States

Academic rigour, journalistic flair

Academic rigour, journalistic flair

A plaque in Russia commemorates the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, whose leaders were executed in August 1952.

Adam Baker/Flickr via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

Stalin’s postwar terror targeted Soviet Jews – in the name of ‘anti-cosmopolitanism’

Published: December 1, 2025 1.16pm GMT

Wendy Z. Goldman, Carnegie Mellon University

A plaque in Russia commemorates the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, whose leaders were executed in August 1952.

Adam Baker/Flickr via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

Stalin’s postwar terror targeted Soviet Jews – in the name of ‘anti-cosmopolitanism’

Published: December 1, 2025 1.16pm GMT

Wendy Z. Goldman, Carnegie Mellon University

Author

-

Wendy Z. Goldman

Wendy Z. Goldman

Professor of History, Carnegie Mellon University

Disclosure statement

I have in the past received funding from the Guggenheim Foundation, the Mellon Foundation, the National Council for Eurasian and East European Research, the ACLS, and the National Endowment for the Humanities. I am not currently receiving funding from any external organization.

Partners

Carnegie Mellon University provides funding as a member of The Conversation US.

View all partners

DOI

https://doi.org/10.64628/AAI.346uth3vf

https://theconversation.com/stalins-postwar-terror-targeted-soviet-jews-in-the-name-of-anti-cosmopolitanism-265562 https://theconversation.com/stalins-postwar-terror-targeted-soviet-jews-in-the-name-of-anti-cosmopolitanism-265562 Link copied Share articleShare article

Copy link Email Bluesky Facebook WhatsApp Messenger LinkedIn X (Twitter)Print article

Many Americans know of Josef Stalin’s Terror of the late 1930s, during which more than 1 million people were arrested for political crimes, and over 680,000 executed.

Fewer know about the repressions that began after World War II and ended with Stalin’s death in 1953. Much like the repressions of the 1930s, they involved fabricated plots, arrests, coerced confessions and purges. Unlike the Terror of the 1930s, they were accompanied by a wave of state-sponsored antisemitism – including the purge of Jews from multiple occupations and unwritten quotas that limited their professional and educational opportunities.

The abolition of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee on Nov. 20, 1948, and the arrest and execution of its members was central to this postwar assault. The committee’s elimination was accompanied by an “anti-cosmopolitan” campaign emphasizing Russian nationalism, Soviet patriotism and anti-Westernism. In certain ways, the campaign served as the mirror image of anti-communist and jingoistic propaganda in the United States at the time.

“Rootless cosmopolitan” became code for “Jewish,” and dismissals swept the arts, sciences and media. The Ministry of State Security arrested Jewish industrial leaders for sabotage and, in 1953, fabricated “the Doctor’s Plot,” which accused a group of predominately Jewish doctors who treated Kremlin officials of trying to assassinate Stalin and other party leaders.

Peretz Markish, one of many Jewish artists and leaders persecuted in the ‘anti-cosmopolitan’ campaign, was executed on the ‘Night of the Murdered Poets.’

Central Archive of the Federal Security Service of the Russian Federation (Moscow) via Wikimedia Commons

Peretz Markish, one of many Jewish artists and leaders persecuted in the ‘anti-cosmopolitan’ campaign, was executed on the ‘Night of the Murdered Poets.’

Central Archive of the Federal Security Service of the Russian Federation (Moscow) via Wikimedia Commons

The very idea of an antisemitic campaign following the massive Soviet losses in World War II presents an enigma. Of the 6 million Jews murdered in the Holocaust, almost 2 million were murdered by the Nazis on Soviet soil. Why would Soviet leaders, who fought a bitter and costly war to defeat fascism, choose to attack the very group that the Nazis tried to annihilate?

My forthcoming book, “Stalin’s Final Terror: Antisemitism, Nationality Policy, and the Jewish Experience,” addresses this difficult question.

Clashing with the state

The Soviet state created the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee in 1942 to aid the war effort at home and abroad. Its chairman, Solomon Mikhoels, was a renowned Yiddish actor and director of the State Yiddish Theater – one of the many cultural and scientific luminaries who led the committee.

The committee made an enormous contribution to the war effort, sending thousands of articles about fascism, the Jewish war experience and the Red Army for publication in the foreign press. Mikhoels and writer Itsik Fefer toured the United States, Mexico, Canada and Great Britain, where they were welcomed by rapturous crowds and raised millions of dollars.

In 1943, as the Red Army began liberating Soviet territories from German occupation, the committee was inundated by letters from surviving and returning Jews. Committee leaders tried to help people reclaim their homes, to distribute foreign aid and to identify and commemorate sites of Nazi war crimes. They wrote to Stalin suggesting the creation of a Jewish national republic in Crimea to replace destroyed communities in Ukraine, Belorussia and Russia.

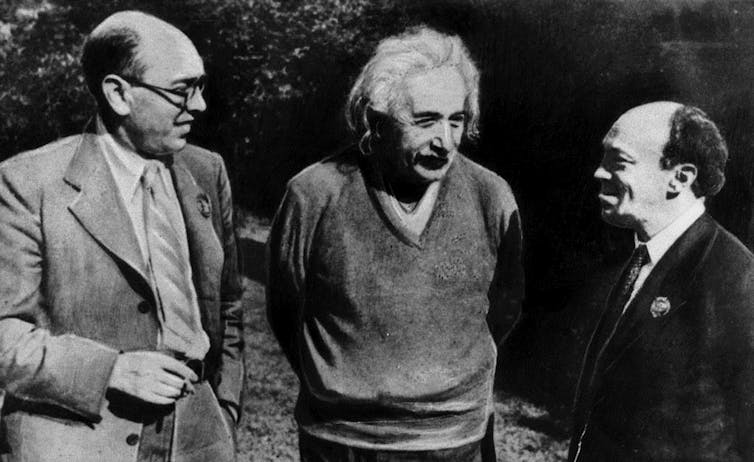

Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee members Itsik Fefer, left, and Solomon Mikhoels, right, speak with Albert Einstein during their international tour.

Mondadori Publishers/Getty Images via Wikimedia Commons

Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee members Itsik Fefer, left, and Solomon Mikhoels, right, speak with Albert Einstein during their international tour.

Mondadori Publishers/Getty Images via Wikimedia Commons

But the state deemed these unsanctioned activities expressions of “bourgeois Jewish nationalism.” Some Communist Party leaders even insinuated that the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee was being used by spies, and advocated its elimination.

The minister of state security, V.S. Abakumov, convinced Stalin that Mikhoels was spying for Jewish organizations in the United States, but Mikhoels was too well known at home and abroad to be arrested. In January 1948, Mikhoels was lured to a house on the outskirts of Minsk, crushed by a truck and dumped on a deserted road.

The murder, disguised as an accident, signaled a turning point in the government’s policy toward Soviet Jews. In November 1948, the government abolished the committee as “a center of anti-Soviet propaganda.” Fifteen of its leaders were arrested over the following months. The state shuttered the Yiddish publishing house, press, theaters, literary journals and writers association, and arrested hundreds of Yiddish cultural figures.

Unbowed in court

The Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee’s leaders were charged with bourgeois nationalism, treason and espionage. Tortured in prison and kept in cramped, freezing cells, they were forced to confess.

The Ministry of State Security hoped to stage a public show trial, but as soon as the physical coercion stopped, the defendants began to retract their confessions and write letters of protest. The evidence was based on these extracted confessions, and the state feared an international outcry.

After the group had already spent more than two years in prison, the case was reopened. M.D. Riumin, the new head of the investigatory unit, was intent on showing that the defendants directed Jewish nationalist organizations that infiltrated the government at every level. After new interrogations, an indictment was drawn up, sent to Stalin and approved by the Politburo.

A secret trial began in May 1952. Despite being physically broken, the defendants presented a powerful rebuttal.

Solomon Lozovskii, pictured here in the 1930s, had led the Red International of Labor Unions.

brandstaetter images/Hulton Archive/Imagno/Getty Images

Solomon Lozovskii, pictured here in the 1930s, had led the Red International of Labor Unions.

brandstaetter images/Hulton Archive/Imagno/Getty Images

Solomon Lozovskii, an old revolutionary and former deputy foreign minister, shredded the state’s accusations. Historian Iosif Iuzefovich retracted his confession and told the court that after numerous beatings, “I was ready to confess that I was the pope’s own nephew, acting on his direct personal orders.” Boris Shimeliovich, the director of a leading Moscow hospital, testified that he had received over 2,000 blows to his buttocks and heels. Even the chairman of the court began to doubt the charges.

Yet the defendants were convicted. Thirteen of the 15 were executed on Aug. 12, 1952. The executions were later commemorated as “The Night of the Murdered Poets, though only five of the victims were poets. Solomon Bregman, a labor leader, died in prison; Lina Shtern, a renowned scientist, was sentenced to exile.

After Stalin’s death, the defendants were exonerated. The case only became public, however, in 1988, when the country began a full reckoning with the Stalin era.

Lina Shtern, shown here in the 1930s, was well known for her scientific research on the blood-brain barrier.

Dephot/ullstein bild via Getty Images

Lina Shtern, shown here in the 1930s, was well known for her scientific research on the blood-brain barrier.

Dephot/ullstein bild via Getty Images

The final Terror

How do we explain this final Terror?

Jews had benefited enormously from the revolution in 1917, which eliminated czarist oppression, granted them equal rights and opened new educational and employment opportunities. They entered professions and held leading posts in the Communist Party. They were considered an official nationality, like Ukrainians, Uzbeks, Armenians and hundreds of other groups in the new Union of Soviet Socialist Republics.

Yet after the war, the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee’s efforts to help Jewish survivors and commemorate the Holocaust were not acceptable to the state, which minimized the singularity of Jewish wartime experiences. The government identified advocacy solely on behalf of Jews, either at home or abroad, as "bourgeois nationalism” or Zionism.

Amid the intensifying Cold War, the government sought to mobilize popular support by resurrecting Russian nationalism, once an anathema to socialist revolutionaries. It reestablished many czarist discriminatory policies, creating obstacles to Jewish advancement and education. Despite the government’s initial support for the new state of Israel, it blocked the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee from participating in Jewish international organizations, which it viewed as a conduit for Western spies and Jewish nationalism.

Some historians believe that Stalin was preparing a larger Terror, including the deportation of the Jewish population, but his plans were disrupted by his death in 1953. Others disagree, asserting a lack of evidence.

Yet one point is worth pondering: Using the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, Riumin aimed to build a larger case that would have targeted Jews in every institution for treason. He never succeeded, however, in staging a public trial or launching a wider hunt for enemies throughout the government.

The courage of the defendants thwarted Riumin’s venomous ambition. They testified bravely about their abuse and exposed the falsity of the charges. Revolutionaries committed to the struggle against fascism, they held firm to the end.

- Soviet Union (USSR)

- Russia

- Judaism

- Antisemitism

- Repression

- Stalin

- Anti-fascism

- Religion and society

- Soviet history

Events

Jobs

-

Senior Lecturer, Clinical Psychology

Senior Lecturer, Clinical Psychology

-

University Lecturer in Early Childhood Education

-

Case Specialist, Student Information and Regulatory Reporting

Case Specialist, Student Information and Regulatory Reporting

-

Lecturer in Paramedicine

Lecturer in Paramedicine

-

Associate Lecturer, Social Work

Associate Lecturer, Social Work

- Editorial Policies

- Community standards

- Republishing guidelines

- Analytics

- Our feeds

- Get newsletter

- Who we are

- Our charter

- Our team

- Partners and funders

- Resource for media

- Contact us

-

-

-

-

Copyright © 2010–2025, The Conversation

Senior Lecturer, Clinical Psychology

Senior Lecturer, Clinical Psychology

Case Specialist, Student Information and Regulatory Reporting

Case Specialist, Student Information and Regulatory Reporting

Lecturer in Paramedicine

Lecturer in Paramedicine

Associate Lecturer, Social Work

Associate Lecturer, Social Work