- Culture

- Film

- Features

The award-winning director has endured imprisonment and censorship by his country’s leaders, who insist his movies are ‘anti-government propaganda’. Days before he was sentenced to further jail time, he spoke to Adam White about his new film ‘It Was Just an Accident’, and why making art always trumps dire consequences

Wednesday 03 December 2025 14:24 GMTComments

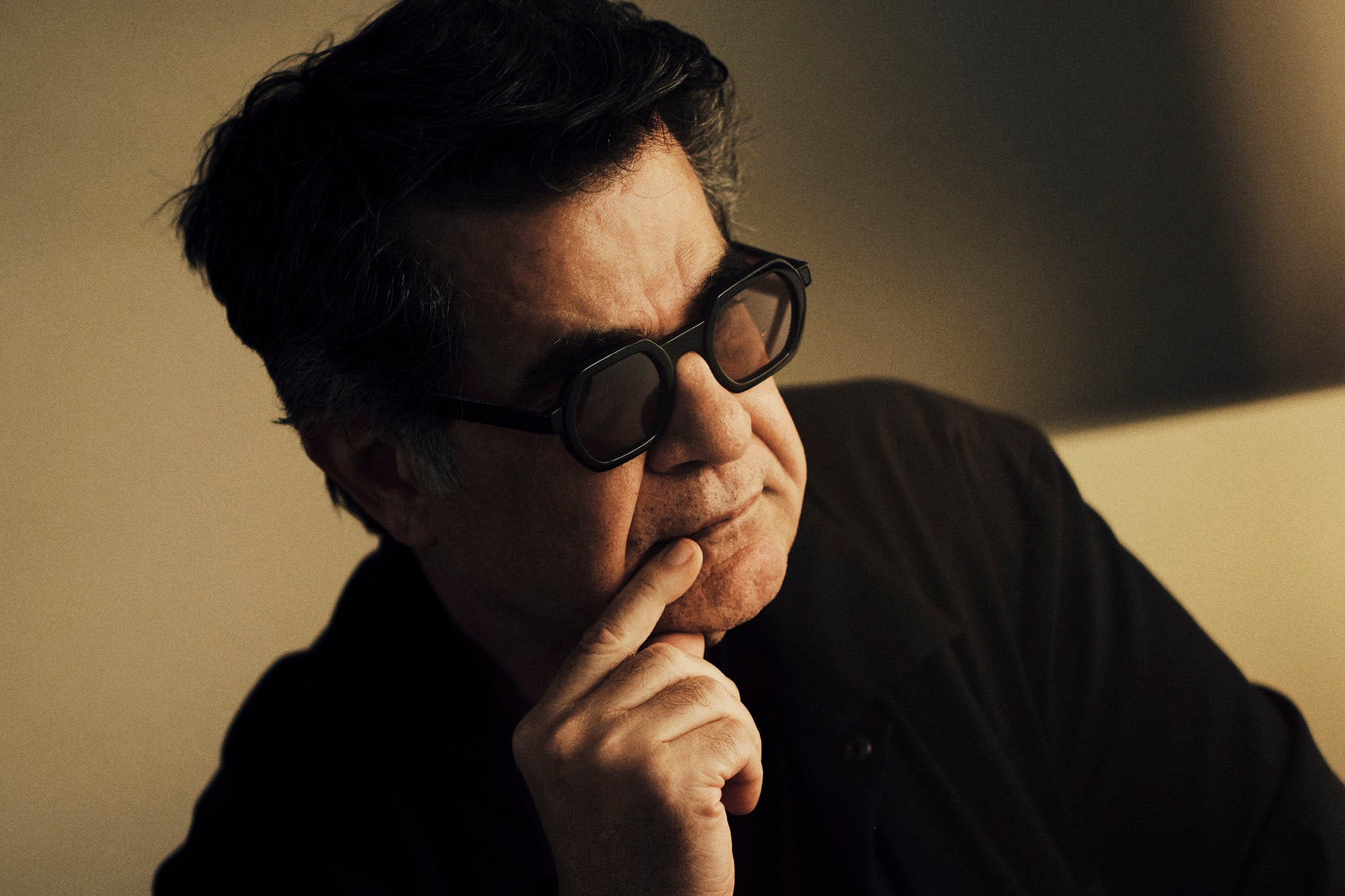

Wednesday 03 December 2025 14:24 GMTComments open image in gallery‘Should I become one of these people sitting and complaining about how difficult things have become? Or should I rather try and find a way? In the end, I decided to do whatever it took to keep working’ (Getty)

open image in gallery‘Should I become one of these people sitting and complaining about how difficult things have become? Or should I rather try and find a way? In the end, I decided to do whatever it took to keep working’ (Getty)

Get the latest entertainment news, reviews and star-studded interviews with our Independent Culture email

Get the latest entertainment news with our free Culture newsletter

Get the latest entertainment news with our free Culture newsletter

Email*SIGN UP

Email*SIGN UPI would like to be emailed about offers, events and updates from The Independent. Read our Privacy notice

Jafar Panahi wants to go home. “To be honest, my time is being totally wasted with all this travel,” the filmmaker tells me from a New York hotel room, amid a months-long international press tour. “I cannot wait for it to be over and to go back to Iran, sit down, and get to work.” As much a professional mischief maker as he is a political dissident, simultaneously despised and feared by the Iranian authorities, Panahi cracks a wry smile. “I want to suggest a legal solution going ahead,” he says, tongue planted firmly in cheek. “All filmmakers should be banned from leaving their countries so they can actually get some work done.”

On the Thursday afternoon that we speak, the remark makes me laugh. On Monday evening, on hearing the news that Panahi has once again been sentenced to prison by the government of his homeland, it makes me wince. But if anyone is better able to face physical and existential threat, it is a man who has defied authoritarian rule for 25 years, persevering through a 20-year travel ban, two previous stints in jail, and a block on making films.

Speaking from behind orange shades, his voice scorched and crackling from a lifetime of cigarettes, Panahi is an enemy of the state in the mode of Fred Hampton or Jane Fonda. He’s brave. Unflappable. Almost intimidatingly cool. His films – among them the tender 1995 drama The White Balloon and this year’s Palme d’Or winner It Was Just an Accident, which is in cinemas this week – are compassionate snapshots of contemporary Iran. They often allude to, but aren’t necessarily fueled by, themes of state oppression, misogyny and police brutality, and have been widely embraced worldwide: It Was Just an Accident is expected to receive Oscar attention next year, and Panahi was busy collecting three Gotham Awards in New York on Monday – for Best Director, Best Original Screenplay and Best International Feature – when he learnt of his new sentencing. Many of his films are also, according to Iran’s rulers, “anti-government propaganda”, and subject to constant assault.

Panahi’s last nine films have all been banned in the country, and despite his own international accolades (he has won top prizes at the Berlin and Venice film festivals), he has faced repeated censure: in 2010, he was sentenced to six years in prison for “propaganda against the state”, and released after three months. In 2022, he served a further seven months, for apparent involvement with anti-government protests, and was only released after embarking on a 48-hour hunger strike. His unexpected latest sentence, which includes a year in prison and a two-year ban on leaving Iran, was a result of unknown “propaganda activities”, his lawyer Mostafa Nili announced on Monday. They will appeal, he added, but Panahi will also return to Iran despite the threat against him. Running away isn’t the 65-year-old’s style.

There have been past opportunities for him to flee, he explains. His 20-year travel ban came to an early end in 2023 after 14 years, and Panahi and his wife left Iran for Paris, where he edited It Was Just an Accident. “But I am not able to adapt to anywhere else,” he says, speaking through Iante Roach, a translator. “The problem lies within myself. I can only live in Iran. I don’t have a profound knowledge of people in other countries – say in England, or France. And if I were to make a film about them, it would only be superficial.”

I just ask that the state tolerates my films at least enough to allow them to be shown

Panahi was formally blocked from making films in 2010, and thought for a moment about accepting his fate. “I was profoundly, psychologically shocked,” he remembers. But the sentencing also coincided with Panahi’s newfound status as an inspiration for younger or aspiring filmmakers. He’d find himself regularly approached by them, who’d ask how they could – like him – make interesting, subversive work under difficult conditions. Many of them had already given up. “I asked myself what I should do,” Panahi says. “Should I become one of these people sitting and complaining about how difficult things have become? Or should I rather try and find a way? In the end, I decided to do whatever it took to keep working.”

What he did was cheekily bend the rules of his own punishment. First he made a documentary about his circumstances, and called it This Is Not a Film. “And then I asked myself what else I could do,” he says. “I thought, well, I can drive – so I can become a taxi driver, but if I am to become a taxi driver, I might as well plant a camera in the taxi and have passengers tell me their stories.” This, then, became his 2015 film Taxi. Another film, a pseudo-documentary called No Bears, was made under strict secrecy in 2021.

open image in galleryMariam Afshari, Mohamad Ali Elyasmehr, Hadis Pakbaten, Majid Panahi and Vahid Mobasseri in ‘It Was Just an Accident’ (Mubi)

open image in galleryMariam Afshari, Mohamad Ali Elyasmehr, Hadis Pakbaten, Majid Panahi and Vahid Mobasseri in ‘It Was Just an Accident’ (Mubi)“The best films made in Iran today are made underground,” he says. “And people find their own ways to make them – many get [government-sanctioned] permits to make a particular film, but then make it differently, or add a subversive message into it.” He bears no ill-will towards more commercially minded movies allowed by Iran’s rulers. “I just ask that the state tolerates my films at least enough to allow them to be shown,” he adds. Only The White Balloon and its 1997 follow-up The Mirror have ever been screened legally in the country.

I ask Panahi if he ever gets a thrill from the act of getting away with it, and successfully making a film under the radar – whatever the context that surrounds them, is it ever a little bit fun? He smiles. “You know, we’re conducting a serious interview, but we’re also laughing quite a bit at the same time,” he says. “Such is life. If you remove laughter from life, everything becomes artificial, and it becomes very difficult.” I take that as a yes.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £9.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

Try for freeADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £9.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

Try for freeADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

It Was Just an Accident is arguably Panahi’s most outwardly political film to date. It concerns Vahid (played by Vahid Mobasseri), a former political prisoner now working as a mechanic, who is convinced that he has encountered the man who violently interrogated him years earlier. He bases this solely off the man’s voice, however, and is aware that he may be mistaken. Vahid abducts him all the same, then enlists help from other dissident friends in deciding what to do with him. It is a tense and often startling movie – never didactic despite its circular discussions about violence and revenge, and builds to a gripping climax shot in one long take.

Panahi’s own experiences in prison shaped the film’s story. “Prisoners have one common experience, and that is being interrogated,” he says. “We are forced to sit down on a chair in front of a wall, without our lawyer present, and with an interrogator asking them questions from behind. What happens to prisoners is that, rather than thinking about the questions and answering them, you become absolutely engrossed in trying to guess and determine who this interrogator is. What do they look like? How old are they? And if I see the owner of this voice outside the prison, will I recognise them?”

open image in galleryEbrahim Azizi in ‘It Was Just an Accident’ (Mubi)

open image in galleryEbrahim Azizi in ‘It Was Just an Accident’ (Mubi)Panahi hasn’t, as far as he knows, encountered his own interrogators in the wild, and isn’t sure how he would react if he did. But he doesn’t want audiences to necessarily be mired in the specifics of the film’s plot – instead he wants them to ask themselves broader questions once they see it. “I really want people to grapple with [the idea of] the cycle of violence,” he says. “Should revenge be allowed to continue, or does it have to end at some point?”

I ask Panahi about the people who appear in his films, who tend to be a mix of actors and non-actors. Like him, they are aware that they are jumping into work that could quite easily put a target on their backs. Does he warn them about the dangers? He shrugs. “They know fully who they’re being asked to work with, and all of them are keen to do something different, too,” he says.

He mentions the Women, Life, Freedom movement, which began in 2022 and saw members of the Iranian public take to the streets in protest against repression and government corruption, spearheaded by an incident in which a woman was arrested by the country’s morality police for not properly wearing her hijab.

“Ever since then, many of us in Iran have decided to do something for the movement, in whatever form that takes,” he says. For Panahi and those in his films, it is achieved through art. “All of us are more concerned with making a good piece of work than whatever the consequences may be.”

open image in galleryCate Blanchett and Juliette Binoche present Panahi with the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival in May (Getty Images)

open image in galleryCate Blanchett and Juliette Binoche present Panahi with the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival in May (Getty Images)As proven by this week, the consequences have now come once again for Panahi. But he won’t – and, he admits, can’t – work or think in any other way. He tells me about the time he made a 30-minute psychological thriller while attending film school, which more or less ripped off the style and visual grammar of Alfred Hitchcock, one of his earliest inspirations.

“It looked great, but it had no soul,” he remembers. So, in possibly his first real act of dissent, he broke into his school’s film lab late at night and stole the negatives of the film. “And then I destroyed them so no one could ever see my movie,” he laughs. “Back then, of course, no one knew who I was. I was simply one of many film students trying to find themselves. Even so, I recognised that your signature has value and that you can’t just put it on any film. I knew what it meant to put your mark on something.”

‘It Was Just an Accident’ is in cinemas from 5 December

More about

IranJafar PanahiJoin our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments