- Culture

- Theatre & Dance

- Features

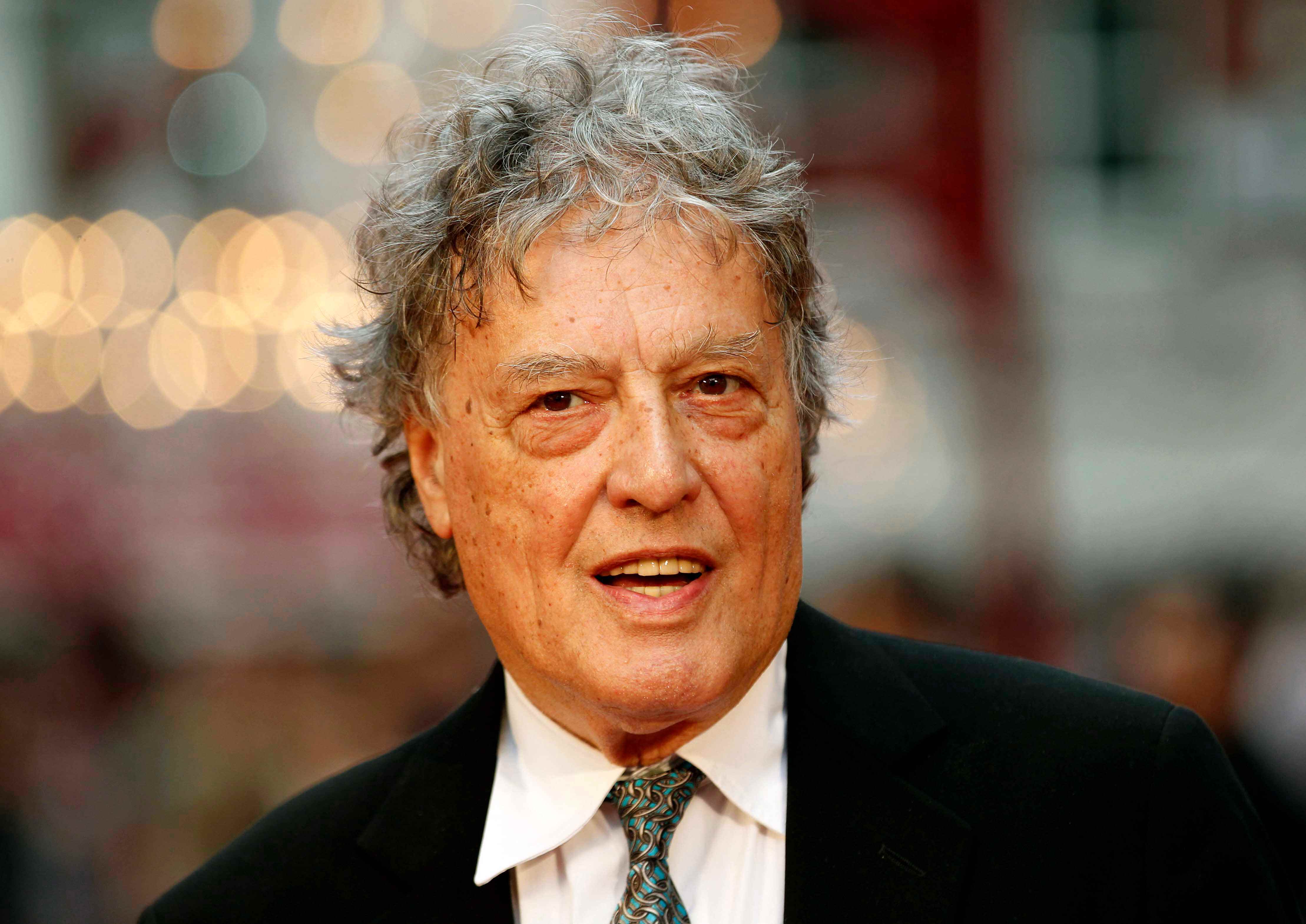

David Lister remembers the brilliant, complicated man whose work explored politics, science, love, Shakespeare, and even rock’n’roll

Monday 01 December 2025 10:35 GMTComments

CloseAward-winning playwright Sir Tom Stoppard dies aged 88

CloseAward-winning playwright Sir Tom Stoppard dies aged 88

Get the latest entertainment news, reviews and star-studded interviews with our Independent Culture email

Get the latest entertainment news with our free Culture newsletter

Get the latest entertainment news with our free Culture newsletter

Email*SIGN UP

Email*SIGN UPI would like to be emailed about offers, events and updates from The Independent. Read our Privacy notice

When I think of Tom Stoppard, I think first of a rather trivial moment in his 1982 play The Real Thing when the protagonist worried about the possibility he might be asked to appear on Desert Island Discs. He didn’t like worthy classical music. And guests who did choose pop tended to choose something arty like Pink Floyd. But he knew to his despair he would end up selecting “Um Um Um Um Um Um” by Wayne Fontana and the Mindbenders.

It's a very Stoppard moment – funny, self-deprecating and in tune with popular culture across the decades.

But then I might think of the visual acrobatics (literally) in his play Jumpers, whose first run I saw in 1972, mixing linguistics, philosophy, circus skills, and a mesmerising Diana Rigg making her entrance swinging on a papier-mâché moon dressed in a fishnet. Jumpers saw Stoppard experiment with mathematical and scientific concepts, which would become pervasive themes in his plays. In this one, the protagonist mused that an arrow shot towards a target had to cover half the distance, and then half the remainder and so on ad infinitum, “and Saint Sebastian died of fright”.

There was also his still underrated and little seen TV play Professional Foul, which aired on BBC in 1977 and combined moral philosophy, international football and totalitarian politics to both hilarious and chilling effect.

Stoppardian was soon to join Pinteresque as an adjective denoting a unique form of theatre, in his case dazzlingly erudite, and startlingly surreal. Whenever I met Sir Tom he was utterly engaging and as self-deprecating as some of his characters. He looked like a rock star with his shaggy mane and Mick Jagger mouth. His whimsical humour was immediately obvious, but he saved his verbal (and sometimes literal) somersaults for his plays, where he explored politics, science, love, Shakespeare, and even rock’n’roll, sometimes all within the same work. Those plays contained multitudes.

And, of course, one must think of his final play, Leopoldstadt in 2020, a searing exploration of a Viennese Jewish family and all their normal domestic romances and travails, until they are caught up in the horror of the encroaching Holocaust. It had poignant echoes of Stoppard’s own recently discovered origins, the stimulus for the play. His mother, scarred by the Second World War and its antecedents, had not told Stoppard of his Jewish roots in Czechoslovakia before they moved to England when he was a child, or that some relatives had died in the Holocaust. Only when family members contacted him in the later years of his life did he embark on writing Leopoldstadt, which was to be his swansong, and in which he appeared to take himself to task in the final scene.

open image in galleryEnglish actors John Thaw and Diana Rigg with Tom Stoppard in 1978 (Getty Images)

open image in galleryEnglish actors John Thaw and Diana Rigg with Tom Stoppard in 1978 (Getty Images)Stoppard was one of a line of emigres, perhaps starting with Joseph Conrad, who brought to their adopted country an intellectual sensibility and a deep love of, and fascination with, its language.

In England he started his career, as I did somewhat later, in journalism in Bristol; and older colleagues there told me with some puzzlement how they remembered him spending much of his time writing plays – of all things. They would have recognised the subversive, young reporter in the now famous anecdote of his editor asking him who the Home Secretary was and Stoppard replying: “I said I was interested in politics, not obsessed with it.” One of his plays, Night and Day, was to be about journalism, with John Thaw cast as the perfect cynical old foreign correspondent thrown into a treacherous run-in with an African dictator and a fling with the journalist-phobic Diana Rigg. All fertile Stoppard territory.

Stoppard’s down-to-earth humour led to numerous memorable moments. When Steven Spielberg phoned him to ask him to write the screenplay for Empire of the Sun (which he eventually did), Stoppard initially turned him down, as he was writing a play for the BBC. “What!” exclaimed Spielberg in disbelief. “You’re giving up the chance of a blockbuster movie for television!” Actually, replied Stoppard, “I’m doing it for the radio.”

open image in galleryStoppard began his career in journalism (Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.)

open image in galleryStoppard began his career in journalism (Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.)And although Stoppard later denied it, I’m inclined to believe the Theatreworld gossip of the time that when his friend Harold Pinter told him he would like to get the Comedy Theatre’s name changed to the Harold Pinter theatre, Stoppard remarked laconically: “You might do better to change your name to Harold Comedy.”

His verbal dexterity was usually too much for reporters who tried to ask him an awkward question. When he was asked about his relationship with the actor Felicity Kendal, he replied: “With these things one can decide whether to contribute or not to contribute. I have decided not to contribute. And that is my contribution.”

Perhaps I slightly regretted that his later, darker, intensely complex and challenging works lacked some of the outright humour of his early years. But he was a playwright never likely to stand still.

His plays are too many and too varied to pay tribute to them all or draw any linear connection. How can you compare his 1967 debut Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, a riotous imagining of what went on behind the scenes with two minor characters in Hamlet, with, say, 1993’s Arcadia, exploring in Stoppardian fashion the relationship between order and disorder, past and present, certainty and uncertainty, through time shifts and the melding together of 19th-century romanticism and chaos theory. It was praised by the Royal Institution of Great Britain as one of the best science-related works ever written. I remember too that The Independent’s science editor at the time wrote a piece taking issue with some of the scientific arguments, and Stoppard, presumably and pleasingly a reader, got in touch with him, not to complain, but enthused at the prospect of debate.

Stoppard was himself a romantic. When someone remarked, inaccurately and ungallantly, and I believe on their wedding day, that his bride Sabrina Guinness had been on the shelf, Stoppard retorted beautifully that he, Stoppard, had been looking on the wrong shelf for too long. He had been looking under biography; he should have been looking under poetry.

We may have lost that complicated, charming, brilliant man. But we will always have the plays, with the wit, the language, the philosophy, and the startling leaps of imagination. We will always have the evidence of why Stoppard dominated and defined British theatre for nearly 60 years.

More about

Tom StoppardDiana RiggDesert Island DiscsJoin our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments